The Spirit of '76

Tomorrow marks the 249th anniversary of the Fourth of July. On July 2, 1776, the Second Continental Congress, meeting in Philadelphia, voted to declare that the thirteen American colonies were free and independent states—no longer subjects of Great Britain. Two days later, on July 4th, the Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence drafted by a committee composed of Thomas Jefferson of Virginia, John Adams of Massachusetts, Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania, Roger Sherman of Connecticut, and Robert Livingston of New York. Jefferson was given the task of actually drafting the document, changes to which were suggested by other members. These actions were the culmination of a series of events that produced widespread public sentiment for independence, what historians call “the Spirit of ‘76.”

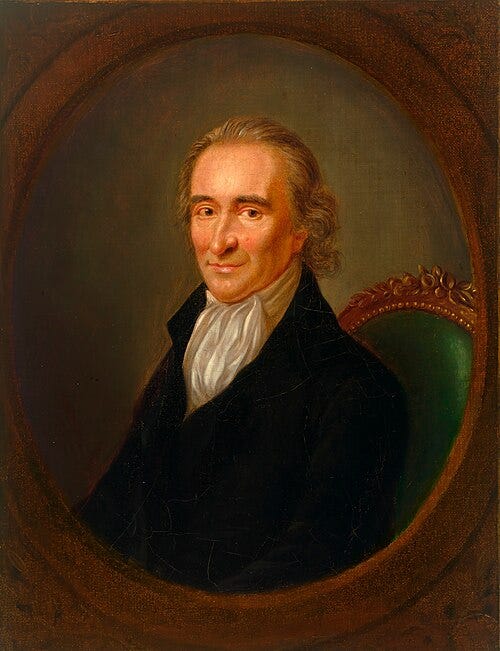

The propagandist most responsible for spreading this spirit was a poor English immigrant named Thomas Paine. Paine was a radical. He detested monarchies, believed in redistribution of wealth, and publicly criticized Christianity in favor of deism, the belief in an impersonal deity or supernatural force that set the universe into rational physical motion and then stepped aside. After American independence, he left for France and joined in the radicalism of the French revolution. While his beliefs were not shared completely by all the framers of the Declaration of Independence, he would have approved of its use of impersonal references to God like “Nature’s God” and “endowed by their Creator.” His little pamphlet, Common Sense, was the publication most widely read and most responsible for popularizing the ideology of independence, the Spirit of ‘76.

Historians and political scientists have debated what it was that moved so many colonists to embrace independence from Britain. A minority of scholars have argued for various economic explanations, but most agree the primary cause was ideological. One important treatment of the subject is Bernard Bailyn’s Pulitzer Prize-winning The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution. Bailyn argued that the revolution was a reaction to British colonial policy, especially taxes imposed by a Parliament with no representation from America. Harkening back to the English Glorious Revolution of 1688 and its English Declaration of Rights, Americans believed that they could only be taxed with their consent, consent expressed through their representatives in Parliament. But if they had no such representation, the British Parliament had no right to tax them. For it to do so was tyranny.

These ideas, refined and spread by American newspaper editors and pamphleteers like Paine and Benjamin Franklin, became so common as to generate a grassroots movement. As we saw yesterday, they were not new ideas; they had been incubating in Britain for eighty years as a result of the writings of liberal Enlightenment philosophers like John Locke. Locke’s philosophy argued that legitimate governments, governments worthy of allegiance, arose from consent of the governed—that prior to government, people lived in a “state of nature,” only organizing laws and governments by agreeing to limit their individual freedoms in exchange for security. People made these arrangements because they perceived them to make their lives happier. They gave up some of their God-given “natural liberty” in the “pursuit of happiness.” Thus, when a government became tyrannical, when it no longer fulfilled what Lockean liberals called the “social contract,” the people retained the right to change that government.

Jefferson, Franklin, Adams, Washington, Paine, and the rest all agreed that these axioms were beyond dispute, indeed self-evident, which is why they voted on July 4th to declare that, “"We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.—That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed,—That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.”

Dr. Bill, Independent will be back Tuesday after the holiday weekend. Have a great Independence Day. Pursue your happiness.